As you know, dear readers, we’re all about inclusive health communication here at We ❤️ Health Literacy HQ. And one topic that we think could use a more inclusive approach is sexual health.

When it comes to sex, it’s easy to assume that everyone has the same general needs and generally experiences the same trajectory. If you think about it, we learn those expectations pretty early in life. When we hear comments like “One day, you’ll get married and have kids of your own,” or “When you get older, you’ll start having feelings for [boys/girls],” we learn that there’s a “normal” path to follow. But the fact is, those oversimplified narratives leave a lot of people out.

In reality, of course, human sexuality is incredibly diverse! And with reproductive rights and anti-LGBTQ+ legislation in the news, it’s more important than ever to create sexual health comm resources that reflect the diverse identities and experiences of our audiences. After all, when people see themselves represented in health materials, they’re more likely to connect with the messages and apply them to their own lives. So this week, we’re bringing you tips for creating inclusive sexual health content.

Tiny housekeeping note before we jump in: This post is part 1, meaning we’ll follow up with a part 2 (we just couldn’t fit it all into 1 post and we think you’ll see why) and maybe additional parts after that! This is a complex and nuanced topic, and we’re here for your opinions and insights — tweet us @CommunicateHlth or respond to this email with comments or ideas for future installments. Okay, back to our first set of tips:

Make the implicit explicit. When you’re writing about sexual health, ditch the euphemisms and offer clear info and action steps. This can look like lots of different things — calling body parts by their “real” names, for example.

Or take CDC’s behavioral recommendations for slowing the spread of monkeypox over the summer, which included mutual masturbation at a distance. And it wasn’t phrased as a vague “self-pleasuring activity” or some such. Rather, CDC said exactly what it meant: “Masturbate together at a distance of at least 6 feet, without touching each other.” How clear! And yes, you may need to explain “masturbate” in plain language depending on the context, but the point is to say what you mean. This makes your content more accessible to everyone, and it’s especially helpful for readers who didn’t have access to comprehensive sex education growing up — which, as you may know, is a rather alarming number of Americans.

Watch out for sneaky assumptions about sexual “milestones.” Many sexual health resources imply that there’s a normal-ish time to start having sex (usually in our teens or early 20s). These not-so-subtle assumptions can alienate people who start having sex later in life — or choose not to have sex at all. Plus, they may remind some readers of awkward or painful moments at the doctor’s office.

For example, asexual people have shared negative experiences with providers who made intrusive comments about their sexual history, framed their orientation as a mental health issue, or treated their asexuality as a medical problem to be solved. So watch out for language that points to a (non-existent) universal sexual experience, like “everyone” or “when you become sexually active.” Instead, frame having sex as a choice that adults can make at any age, based on their own needs and values.

Squash the shame. If there were ever a time to watch out for potentially shameful undertones/overtones/any-direction-tones from (well-intended) health content, this is it. Many of us grew up with all kinds of shame-based messages about sex. It’s easy to see how shame plays a role in religious messaging about abstinence and sexual “purity.” But purity culture affects all of us, and it shows up in public health messaging, too.

For example, some sexual health resources may imply that having sex with multiple partners is bad, or that certain people are at higher risk for STDs simply because of their LGBTQ+ identity. So think carefully about how you’re framing “risky” behaviors and watch out for those unintended shame messages — especially language that conflates a person’s identity and their behaviors. As an antidote to shame, when the context is right, consider emphasizing that sex is an important (and fun!) part of life for many people — and that’s something to celebrate.

And that’s where we’re going to leave it for today — stay tuned for part 2 coming up very soon!

The bottom line: Everyone deserves accessible information about sexual health! Try these tips to make your sexual health content more inclusive.

Tweet about it: Everyone deserves accessible info about #SexualHealth! Check out some tips from @CommunicateHlth to make your sexual health content more inclusive — and stay tuned for more: https://bit.ly/3DAzt54 #HealthComm #HealthLiteracy

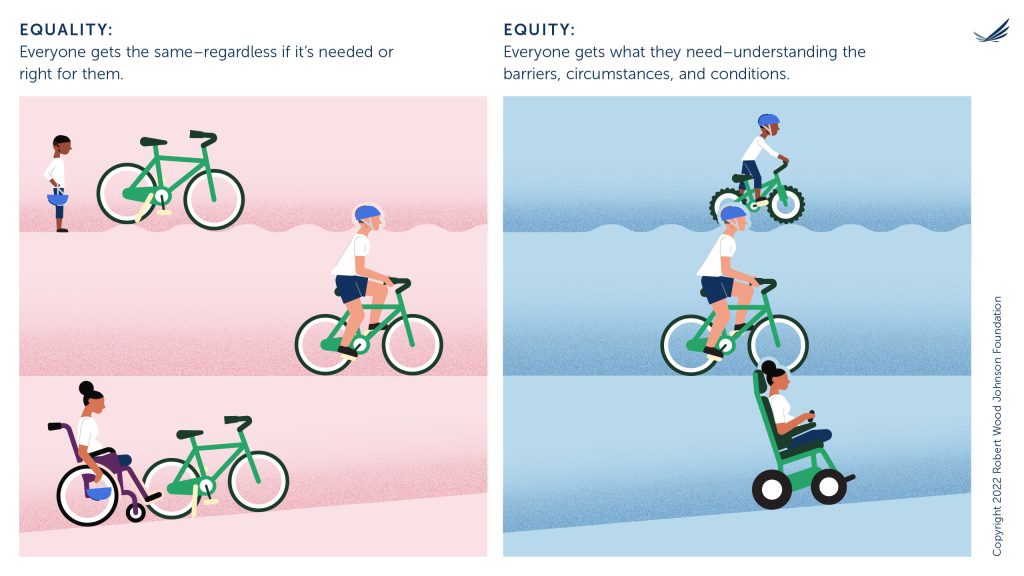

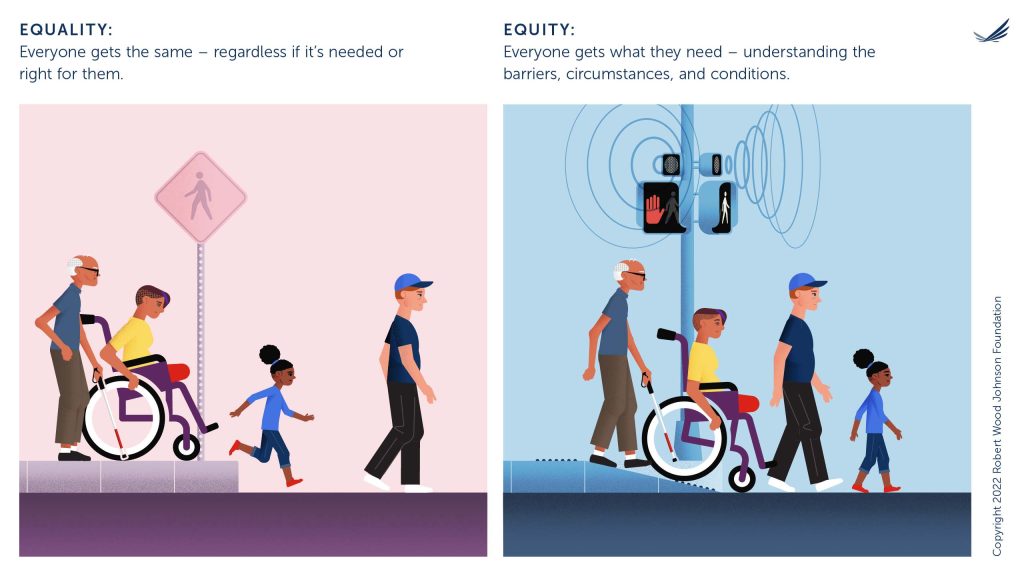

Here at We ❤️ Health Literacy HQ, we’ve been talking a lot (a lot a lot) about equity. You probably have been too, our dearest readers! After all, the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted longstanding inequities that shape health outcomes — inequities rooted in racism, ableism, and other types of discrimination. Talking about ways to center equity in our work is an important first step. But figuring out what equity looks like in real life? That can get tricky. Luckily, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) has some visuals to help us do just that.

Here at We ❤️ Health Literacy HQ, we’ve been talking a lot (a lot a lot) about equity. You probably have been too, our dearest readers! After all, the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted longstanding inequities that shape health outcomes — inequities rooted in racism, ableism, and other types of discrimination. Talking about ways to center equity in our work is an important first step. But figuring out what equity looks like in real life? That can get tricky. Luckily, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) has some visuals to help us do just that.